PISA Tests: How Talking with Parents Affects Russian Pupils’ Financial Literacy

On the financial literacy and global competencies tests of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Russian pupils demonstrate average scores. In their ability to empathise with those experiencing difficulties, they are no different from their peers of OECD countries. This was discussed by experts of HSE University's Institute of Education and the World Bank at a joint seminar.

The international PISA tests, which assess pupils’ functional literacy, have been conducted by the OECD since 2000. Their goal is to assess the quality of education. At the same time, the tasks are determined by experts who do not work in education. The main question they ask is whether 15-year-old school graduates have the necessary knowledge for everyday life.

The tests initially assessed reading and mathematical literacy, and were then supplemented by studies of the level of scientific knowledge. In 2012 and 2015, financial literacy tests were also conducted and in 2018 global competency tests were added.

HSE University’s Institute of Education held a seminar ‘PISA in Russia: New Directions, Results and Challenges’, where participants discussed the results and dynamics of assessments in new disciplines of the international test.

Elena Rutkovskaya, Senior Researcher at the Institute for Strategy of Education Development of the Russian Academy of Education (RAE), explained that the 2018 financial literacy test consisted of 43 questions, a third of which were new. Pupils were asked, for example, which of several provided bank deposit options and mobile phone provider plans are the best deal. Pupils had to demonstrate not only familiarity with financial tools, but also the ability to calculate the short- and medium-term results of their decision and to search and select information. And as a result, they had to demonstrate the ability to choose the best product for themselves.

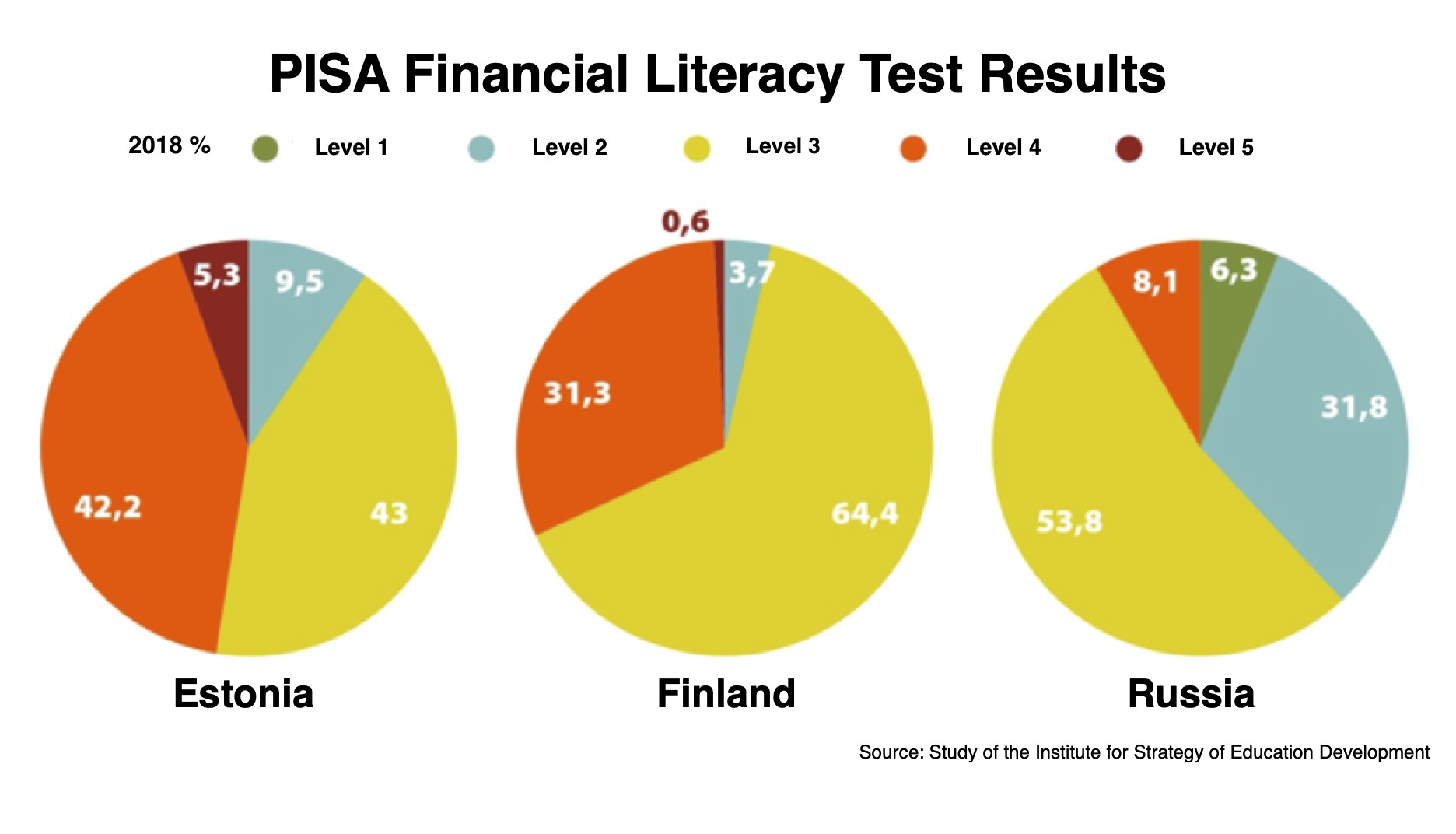

In 2018, Russian pupils ranked 10th out of 21 countries in financial literacy. Compared to 2015, they increased their median score by 9 points, to 495 points, slightly ahead of Spain (492) and behind Lithuania (498). This middle position should not be misinterpreted, cautions Elena Rutkovskaya. Most Russian ninth-graders (85.6%) demonstrated a second or mid-third level of financial literacy, with 8% achieving an advanced level. Whereas the leaders, Estonia and Finland, showed increased and high levels of financial literacy by 47.5% and 32% of test participants.

In nine regions of Russia, where a pilot project to teach financial literacy in schools was conducted jointly with the World Bank, the average score was slightly higher than the national average (496). Nevertheless, the share of those who did not reach the threshold level was three times lower (2% vs. 6.3%).

Information obtained from teachers and through regular conversations with parents on financial topics had a positive impact on Russian pupils’ performance

In this, the Russian participants differed significantly from pupils in OECD countries, where communication with their parents had a negative effect on test results.

Experts from the Institute for Strategy of Education Development also noted that higher financial literacy was shown by Russian pupils who had experience working independently outside the home. Helping parents with household chores and family businesses did not affect the results.

In the first PISA Global Competencies Test, administered in 2018, pupils from 66 countries completed the questionnaire, and pupils of 27 countries completed assignments. Tatiana Koval, Senior Researcher at the Institute for Strategy of Education Development, explained that the questions were divided into three key blocks: studying aspects of local, global and intercultural significance; understanding and appreciating the perspectives of others; and promoting collective well-being and sustainable development.

This test is largely focused on the acquisition of soft skills; it shows how well prepared 15-year-old pupils are to live in a multicultural society; how they are able to evaluate information, formulate arguments, and identify and analyse different opinions.

Russia ranked 14th out of 27 countries, with an average score of 480 points, slightly higher than the average (474) for all participating countries. That is, Russia is a strong mid-level contender. However, very few Russian pupils earned high scores (levels 4 and 5), and their performance revealed insufficiencies in their ability to present and support an argument. In addition, Russian ninth-graders willingly seek out additional information, but rarely use it if the task requires working out a large amount of material.

This, Tatiana Koval believes, suggests that domestic high schools need to pay more attention to information analysis. Russia ranks higher than only two OECD countries, Chile and Colombia, in terms of global competence.

A survey of pupils in 66 countries showed that Russian pupils feel sympathy for people in difficult situations in much the same way as their peers from OECD countries.

In Russia, 61% of pupils surveyed believe that they should do something to help people living in poor conditions, while 67% of pupils of OECD countries believe they should do something

However, Russian pupils are less confident in their own abilities: in Russia only 46% believe they can help solve the world's problems, while the OECD average is 57%.

According to the seminar participants, the COVID-19 pandemic could negatively affect education due to inequality in communication access and necessary equipment. If the lockdown is extended to 8–9 months, children from low-income families may suffer a deterioration in their assimilation of certain subjects. In particular, according to a survey of fifth-graders in Vladivostok schools, the proportion of children with low grades in maths increased by 10%, while self-esteem and the quality of time management have decreased by almost a third. All this requires additional attention from teachers.

Professor Irina Abankina of HSE University’s Institute of Education is concerned that, in her opinion, there is a tendency to increase the use of formal technologies of educational work, which can suppress the development of children. And severe pressure in the management of the educational process deprives schools of initiative. She believes that it is necessary to develop programmes to encourage the development of skills and competencies. It is important to educate children who are flexible and able to participate in the modern world, says the HSE professor.