How Bilingual Brains Work: Cross-language Interplay and an Integrated Lexicon

An international team of researchers led by scientists from the HSE University have examined the interplay of languages in the brains of bilinguals. Using EEG data of Russian-English bilinguals, the authors were the first to demonstrate nearly instant and automatic detection of semantic similarity between words belonging to their two languages, suggesting the existence of an integrated bilingual lexicon in which words are activated in parallel in both languages. The study findings are published in Cortex.

Bilingualism is a widespread phenomenon of growing importance in today's world of globalisation and migration. In the broader sense, bilinguals are people who are able to communicate in two languages. Bilinguals can be 'balanced' or 'non-balanced' depending on the level of language proficiency, and 'early' or 'late' depending on the age of second language acquisition.

An increasing number of studies focus on non-balanced late bilingualism, since most bilinguals belong to this group. The questions of whether bilinguals access the lexicon of each language separately, whether their brains have formed an integrated bilingual lexicon, and how fast they are able to process linguistic information in their second language are widely discussed in research.

Previous research reveals that monolinguals have fast and automatic lexico-semantic access to their language. EEG captures the brain's response to a linguistic stimulus after 50 ms, meaning that a person takes just 0.05 seconds to recall and say the right word. An international team of researchers with the participation of scientists from the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience have examined whether 'late' bilinguals are able to process lexico-semantic information as fast and whether it involves parallel activation of the other language.

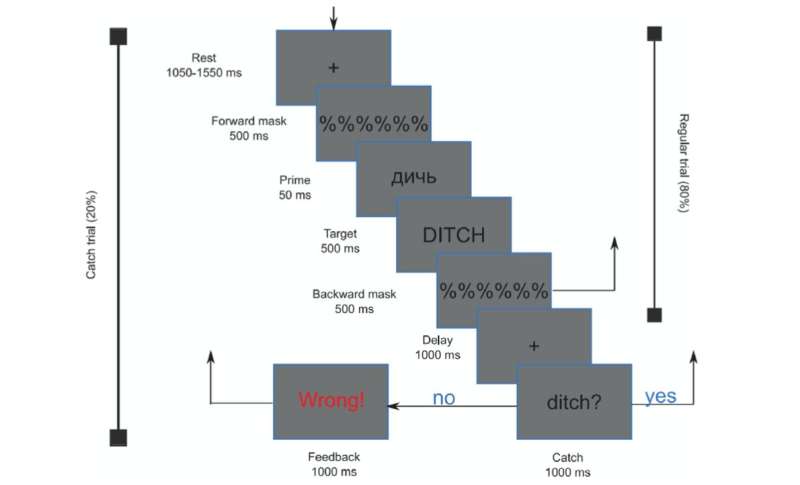

The authors asked 17 HSE University students, native speakers of Russian, to complete a task that involved semantic priming, ie, the mind's tendency to recognise a word faster if it is preceded by a similar one. In bilingual experiments, primes used are usually first- or second-language words which are similar in meaning, sound or spelling to the target word. In most cases, primes are masked so that subjects are not consciously aware of them. In this experiment, Russian words were presented as primes of English targets in conditions of semantic similarity or dissimilarity between the two languages. Stimuli were presented on a computer screen as a sequence: a cross in the middle of the screen to focus on, a series of % symbols as the forward mask, a prime presented for 50 ms followed by a target word, and the backward mask. The subjects were finally presented with a catch word and asked whether it was the same as the preceding target word. Since masks were used and the prime was shown for a very brief period, the prime’s effect on the perception of the target word was subliminal.

The authors recorded the subjects' EEG throughout the experimental session. An amplitude difference was registered at 40–60 ms, which is the earliest crosslinguistic effect reported so far.

Federico Gallo, study co-author, Junior Research Fellow of the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience

'Our findings confirm the existence of an integrated brain network for the bilingual lexicon. In this experiment, Russian primes, similar semantically to the English targets, made it easier for subjects to understand foreign words and shortened their reaction times. Our results suggest that second-language words are activated automatically in bilingual brains, and that cross-language interplay involves left temporo-parietal neural regions.'

However, according to Gallo, although having great temporal resolution, EEG has intrinsic limits when it comes to high-resolution spatial localisation. In the future, the use of MRI or MEG techniques could lead to fundamental discoveries in this area, adding a fine-grained spatial localisation of the phenomena observed in this investigation to the detailed description of their time-course.

Federico Gallo

Junior Research Fellow, Centre for Cognition & Decision Making

See also:

HSE Neurolinguists Create Russian Adaptation of Classic Verbal Memory Test

Researchers at the HSE Centre for Language and Brain and Psychiatric Hospital No. 1 Named after N.A. Alexeev have developed a Russian-language adaptation of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test. This classic neuropsychological test evaluates various aspects of auditory verbal memory in adults and is widely used in both clinical diagnostics and research. The study findings have been published in The Clinical Neuropsychologist.

Researchers at HSE Centre for Language and Brain Reveal Key Factors Determining Language Recovery in Patients After Brain Tumour Resection

Alina Minnigulova and Maria Khudyakova at the HSE Centre for Language and Brain have presented the latest research findings on the linguistic and neural mechanisms of language impairments and their progression in patients following neurosurgery. The scientists shared insights gained from over five years of research on the dynamics of language impairment and recovery.

Neuroscientists Reveal Anna Karenina Principle in Brain's Response to Persuasion

A team of researchers at HSE University investigated the neural mechanisms involved in how the brain processes persuasive messages. Using functional MRI, the researchers recorded how the participants' brains reacted to expert arguments about the harmful health effects of sugar consumption. The findings revealed that all unpersuaded individuals' brains responded to the messages in a similar manner, whereas each persuaded individual produced a unique neural response. This suggests that successful persuasive messages influence opinions in a highly individual manner, appearing to find a unique key to each person's brain. The study findings have been published in PNAS.

'We Are Creating the Medicine of the Future'

Dr Gerwin Schalk is a professor at Fudan University in Shanghai and a partner of the HSE Centre for Language and Brain within the framework of the strategic project 'Human Brain Resilience.' Dr Schalk is known as the creator of BCI2000, a non-commercial general-purpose brain-computer interface system. In this interview, he discusses modern neural interfaces, methods for post-stroke rehabilitation, a novel approach to neurosurgery, and shares his vision for the future of neurotechnology.

Smoking Habit Affects Response to False Feedback

A team of scientists at HSE University, in collaboration with the Institute of Higher Nervous Activity and Neurophysiology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, studied how people respond to deception when under stress and cognitive load. The study revealed that smoking habits interfere with performance on cognitive tasks involving memory and attention and impairs a person’s ability to detect deception. The study findings have been published in Frontiers in Neuroscience.

'Neurotechnologies Are Already Helping Individuals with Language Disorders'

On November 4-6, as part of Inventing the Future International Symposium hosted by the National Centre RUSSIA, the HSE Centre for Language and Brain facilitated a discussion titled 'Evolution of the Brain: How Does the World Change Us?' Researchers from the country's leading universities, along with health professionals and neuroscience popularisers, discussed specific aspects of human brain function.

‘Scientists Work to Make This World a Better Place’

Federico Gallo is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Cognition and Decision Making of the HSE Institute for Cognitive Research. In 2023, he won the Award for Special Achievements in Career and Public Life Among Foreign Alumni of HSE University. In this interview, Federico discusses how he entered science and why he chose to stay, and shares a secret to effective protection against cognitive decline in old age.

'Science Is Akin to Creativity, as It Requires Constantly Generating Ideas'

Olga Buivolova investigates post-stroke language impairments and aims to ensure that scientific breakthroughs reach those who need them. In this interview with the HSE Young Scientists project, she spoke about the unique Russian Aphasia Test and helping people with aphasia, and about her place of power in Skhodnensky district.

Neuroscientists from HSE University Learn to Predict Human Behaviour by Their Facial Expressions

Researchers at the Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience at HSE University are using automatic emotion recognition technologies to study charitable behaviour. In an experiment, scientists presented 45 participants with photographs of dogs in need and invited them to make donations to support these animals. Emotional reactions to the images were determined through facial activity using the FaceReader program. It turned out that the stronger the participants felt sadness and anger, the more money they were willing to donate to charity funds, regardless of their personal financial well-being. The study was published in the journal Heliyon.

Spelling Sensitivity in Russian Speakers Develops by Early Adolescence

Scientists at the RAS Institute of Higher Nervous Activity and Neurophysiology and HSE University have uncovered how the foundations of literacy develop in the brain. To achieve this, they compared error recognition processes across three age groups: children aged 8 to 10, early adolescents aged 11 to 14, and adults. The experiment revealed that a child's sensitivity to spelling errors first emerges in primary school and continues to develop well into the teenage years, at least until age 14. Before that age, children are less adept at recognising misspelled words compared to older teenagers and adults. The study findings have beenpublished in Scientific Reports .